This is the first article in an intended series covering all aspects of Supply Chain Management.

So why not "Let's talk Supply Chain Management", well two reasons really;

1. It's just not as catchy.

2. Because it is my belief, based on nearly 30 years as a practising supply chain manager/ consultant/ interim and software developer and implementer, that planning is at the heart of managing supply chains. Without planning, done well and properly, supply chain management is just firefighting.

So although I will cover many topics which are not strictly planning the series will, nevertheless, be called "Let's Talk Planning".

What is Planning?

In it's most generic form planning is the practise of putting together a series of actions intended to achieve a specific end point.

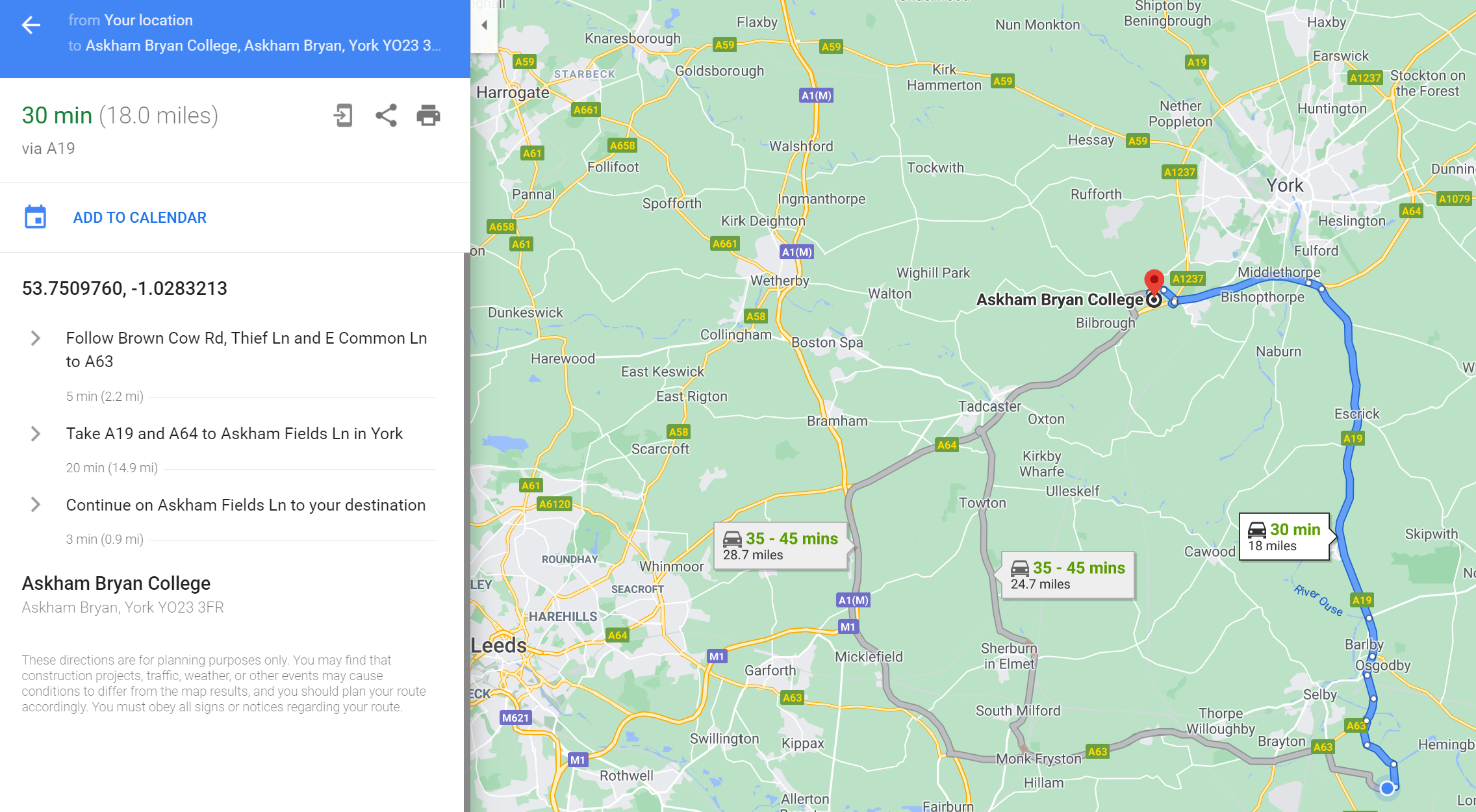

So we might plan to go from A to B and so a plan would involve the steps needed to arrive at B, but then that throws up a whole heap of questions.

- When do you want to arrive? (or when do you want to leave?)

- What method of transport do you intend to use?

- Are you travelling alone?

- What do you need to take with you?

- Do you want to visit anywhere on the journey?

etc.

So now we need to define planning as:

The series of actions which, given a starting point, will deliver the end point and/or any transitional goals by the specified time and via any intermediate points using the defined mechanisms.

There is another type of plan which is simply a series of actions which we are going to carry out regardless of the consequences but this is rarely of use in business or supply chain management. There is one type of planning which comes close to this - Demand Planning - but even here it is rare that we can simply plan or accept into our plans a series of actions (ours or our customers) without thinking through the impact on other parts of the business and other customers.

Within Supply Chain Management there are several areas of planning including:

- Demand Planning,

- Supply Planning,

- Capacity Planning,

- Production Planning,

- Labour Planning and

- Materials Planning.

Some of these overlap or are subordinate to others, in future articles I will cover each in more detail.

The Starting Point

For each of the above we need to be able to specify the starting position with reference to a wide range of parameters. Time is of course one of these but others will include Inventory, Customer Orders (fulfilled, part fulfilled and not fulfilled) and Inbound Inventory. Occasionally (very occasionally these days) a business may be able to have a regular point in time when everything is at a standstill and so it is possible to capture inventory and inbound/outbound positions precisely, more often though it is necessary to artificially create such a point in a constantly moving supply chain. It is VITAL that the measured criteria match up as exactly as possible.

It is no use having an inventory snapshot at one point which is adrift from the points of measurement of customer order status and inbound inventory status. If the points of measurement do not match we will either over count or undercount inventory with possible disastrous consequences.

So we must ensure we define all aspects of the starting point precisely and unambiguously only then will our plans be built on solid foundations.

The Goals

Unlike planning a journey supply chain planning rarely has a fixed end point (a possible exception being when planning a promotional or other activity, or a new product launch). So the goals in these types of planning are usually about achieving certain results either as an ongoing thing or at certain specific points of time.

e.g. To maintain 98.5% casefill for all products and all customers.

or

To maintain 99.8% OTIF through promotion X whilst not exceeding y thousand cases of inventory.

In each of these cases, and in fact in most types of supply chain planning, it is necessary to manage several inputs, outputs and metrics and indeed there may be many different goals and so the plan must ensure that each of these is managed and the goals met. Nevertheless the plan remains the series of actions that must be made in order to achieve these things, the actions are one of the key outputs of the planning process and must be clear and in sufficient detail that they can be communicated and followed.

The actions are what makes a plan different from a forecast, a forecast is a series of things which we believe will happen whereas a plan is a series of things we intend to make happen!

Static or Dynamic?

Over the years I have experienced many situations where the plan is regarded as static; manufacturing may say, "You've told us what to make and that's what we're going to do". Sometimes these fixed actions may be for many weeks or even months.

Is this valid?

Returning to our planned journey analogy would you expect the journey plan to remain static in the face of other changes? For example if you came across a closed road, or saw a signpost to something that was of interest?

Isn't it likely that you would adjust the planned actions in these circumstances? Of course you would take into account the goal(s) of the journey and ensure that these would not be compromised but any plan must be able to be revised in the event of changes to the circumstances or requirements.

The same is true, of course, in supply chain planning, sometimes customer demand will change or there will be changed supply deliveries. In these cases the planned actions need to be revisited and, IF POSSIBLE, revised to accommodate changed circumstances. The goals of the plan must take precedence and the actions be revised where possible to maintain the goals.

Of course there will be times when the actions cannot be changed or where there are cost or other performance implications of doing so and in these circumstances it may be necessary to compromise other aspects of the plan and to create a new plan which delivers the best possible outcomes.

We should not fall into the trap of thinking it is the actions that are unchangeable - otherwise we run the risk of carrying on driving down a road which now terminates with a large hole! (THIS PARAGRAPH SHOULD BE SHARED WITH MANUFACTURING AND PURCHASING COLLEAGUES - changing the plan is NOT a failure if it is done so to continue to deliver the goals and does not fatally compromise some other metric).

Validity

Finally the plan must be deliverable, a plan which is not achievable or in which the actions cannot be made is not a valid plan.

A journey plan which assumes average speeds of 100mph whilst driving a 2CV is not going to be successful.

A plan which makes invalid assumptions about available capacity, waste levels or run rates is not a valid plan!

This may be one of the most common mistakes planners make - they allow invalid assumptions into the plan which render it unachievable. Ultimately they will be accountable to the non delivery of such a plan.

So we can now define a plan as:

A series of achievable, revisable, actions which build from a starting position to deliver a series of goals using

defined resources and with specified inputs and outputs at specific time points.

Next up I will discuss briefly each of the types of supply chain planning defined.

Comments powered by CComment